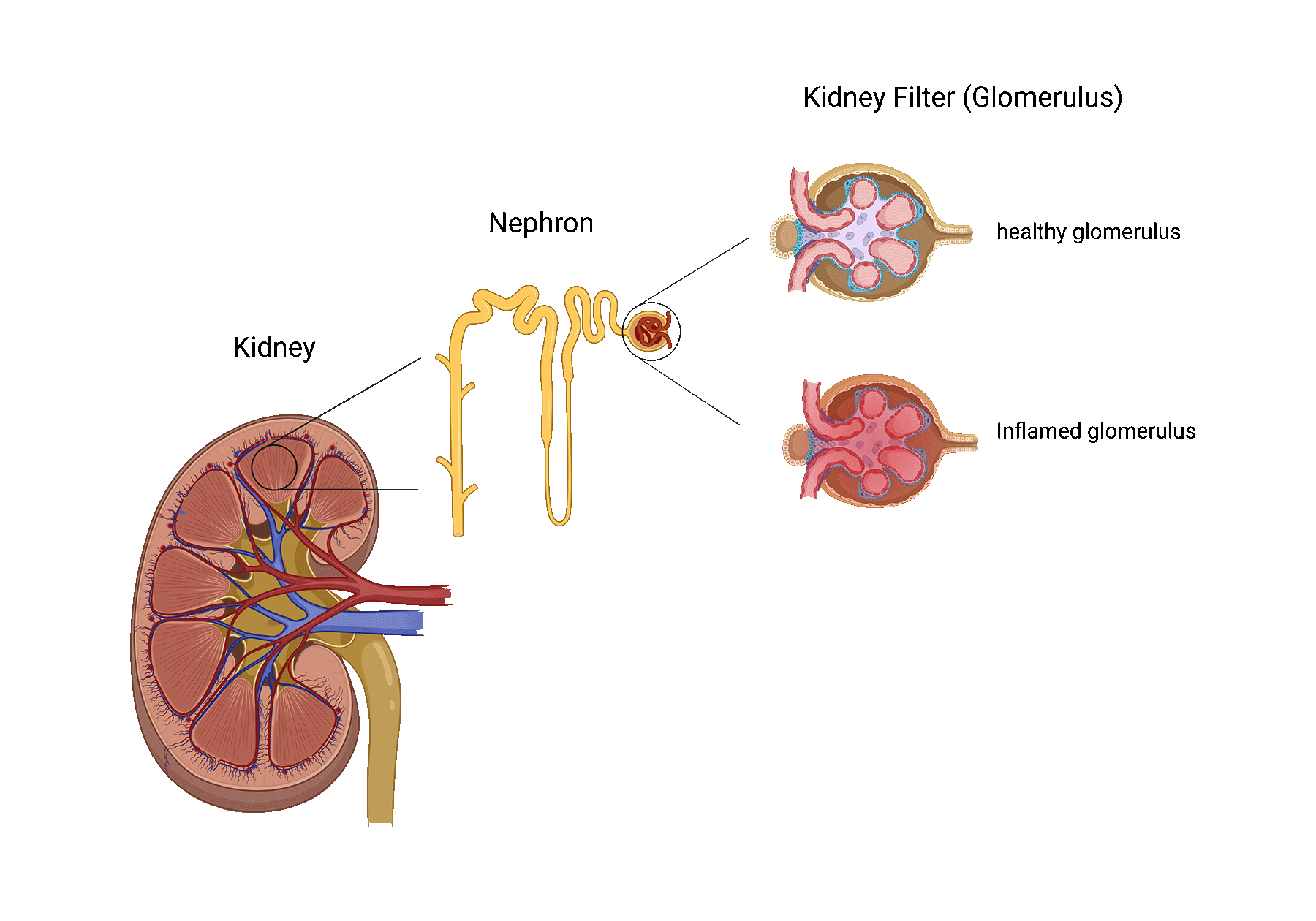

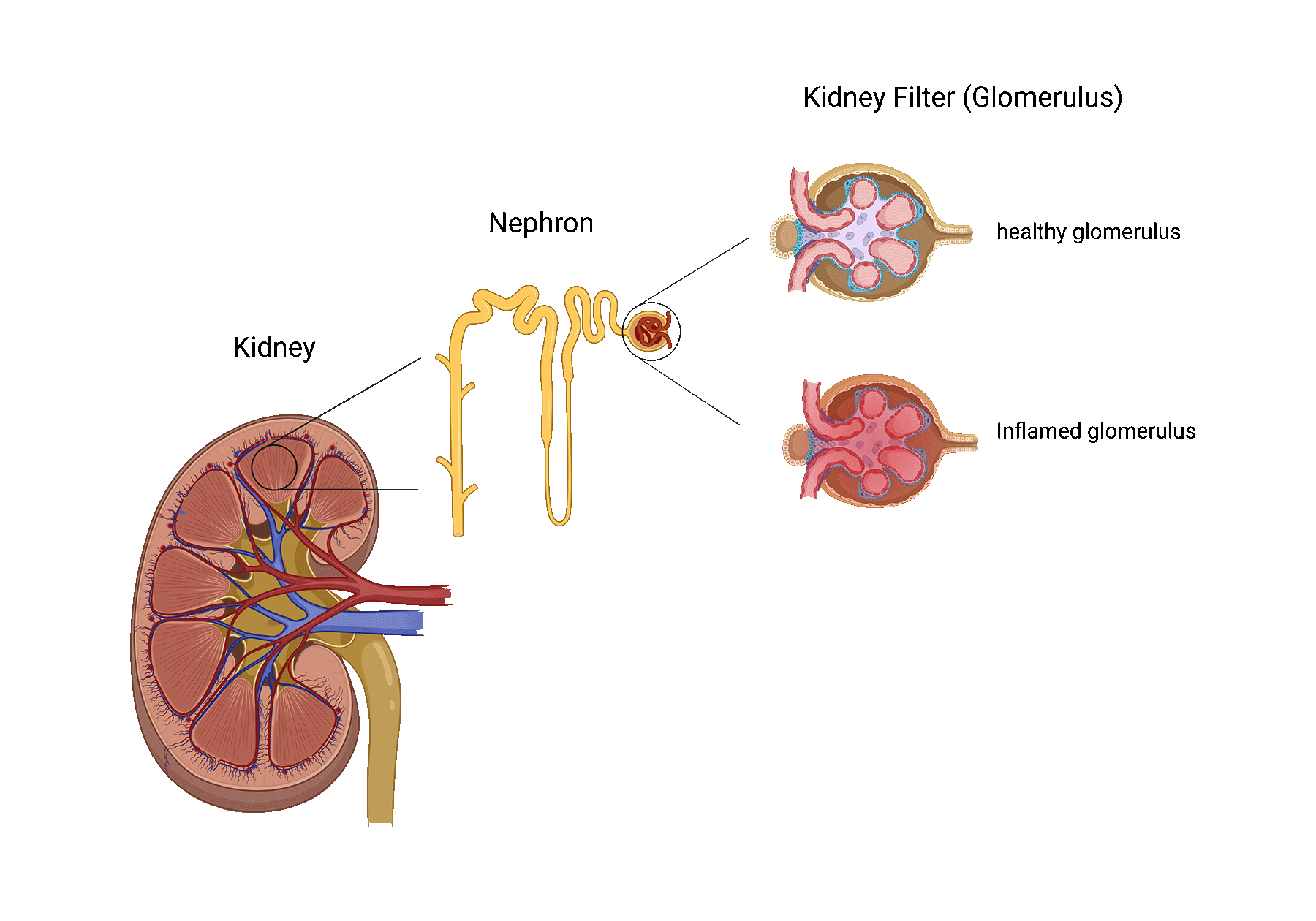

Glomerular disease describes a process in which the kidney’s filters, also known as the glomeruli, are injured.

Although highly dependent on the underlying cause, certain glomerular diseases can progress to end-stage kidney disease, requiring patients to receive a transplant or initiate dialysis.

A kidney transplant is the best treatment option for most patients with end-stage kidney disease. Unfortunately, a transplant is not considered a cure for glomerular disease patients, as recurrence following kidney transplantation may occur.

The recurrence of glomerular disease often damages the transplanted kidney, shortening its lifespan.

Preventing glomerular disease recurrence in causing injury to the newly transplanted kidney still represents one of the biggest challenges for clinicians and scientists worldwide.

The frequency and impact of recurrence after transplantation are highly dependent on the subtype of glomerular disease that led to the failure of the patient’s native kidneys.

Below, find out more about the most common glomerular disease subtypes that can recur after transplant.

Glomerular disease recurrence is frequently asymptomatic and only suspected by a change in specific blood and/or urine tests. In more aggressive cases, a patient may present with the following:

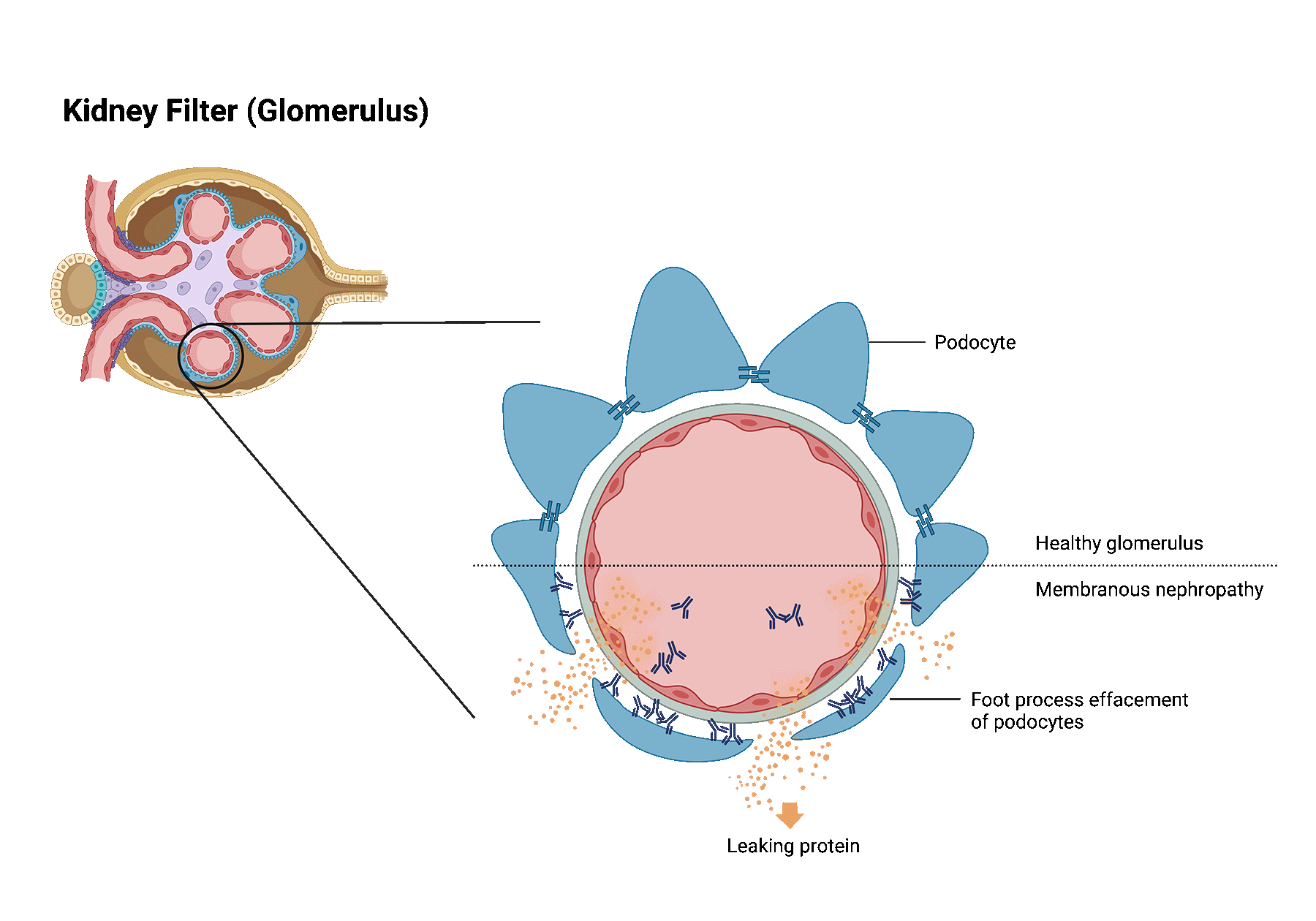

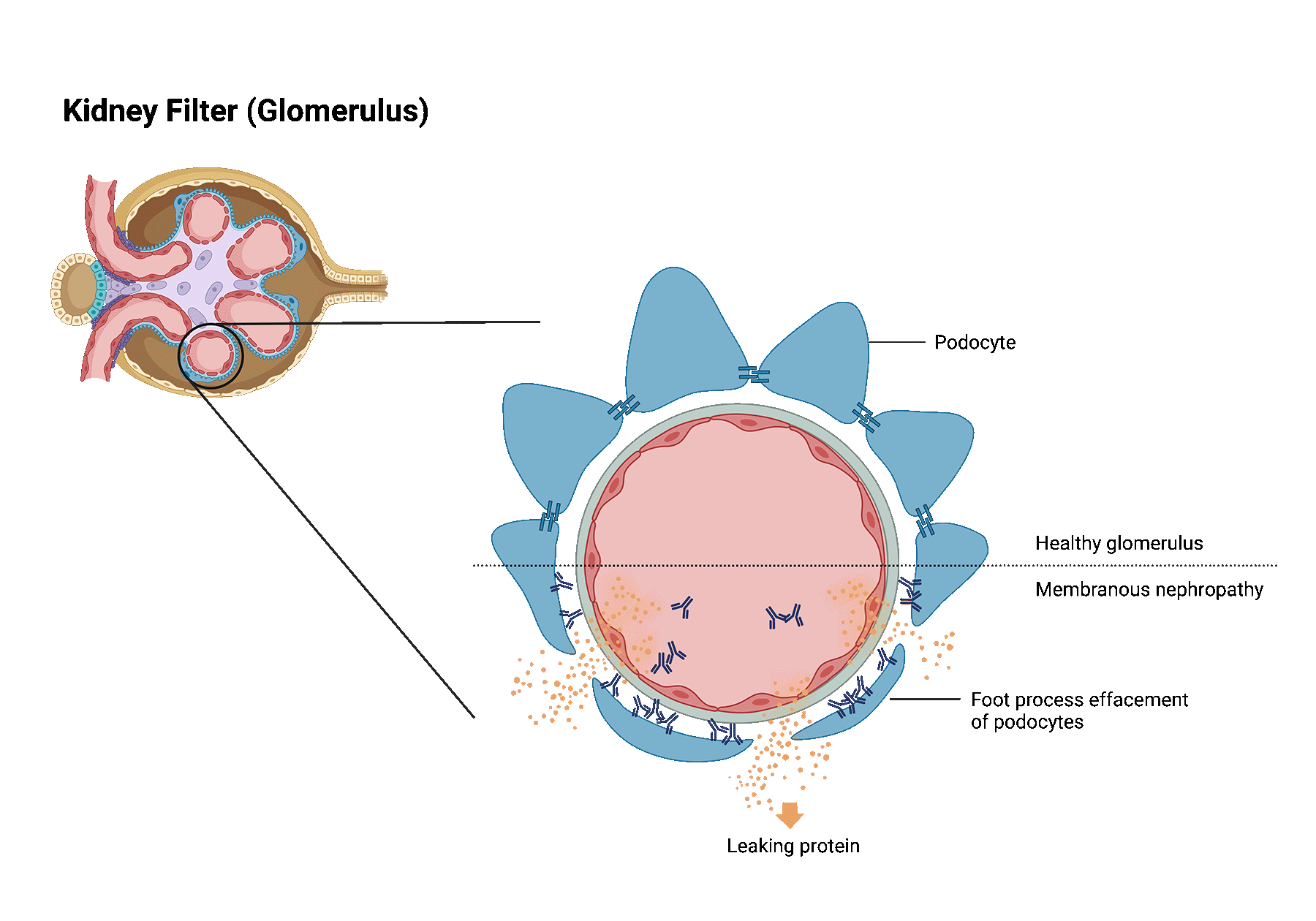

Membranous nephropathy is one of the most common causes of nephrotic syndrome in western countries. In patients with membranous nephropathy, the autoimmune system turns against the tiny filters of the kidneys (aka, glomeruli). Normally, the kidney filters are responsible for filtering toxins and removing extra fluids from the blood, while preventing the passage of most proteins into the urine. When the kidney filters are injured, loss of protein into the urine may occur and when severe, may lead to a syndrome called nephrotic syndrome.

Patients with nephrotic syndrome frequently develop significant swelling in addition to large amounts of protein leakage into the urine.

Despite treatment, almost one-third of patients with membranous nephropathy develop kidney failure.

It is estimated that membranous nephropathy recurs in 30% of patients that received a transplant. Recurrence is most often diagnosed within the first few years after transplantation. The best way to identify membranous nephropathy recurrence in the transplanted kidney is through a kidney biopsy.

It is still poorly understood why the immune system in membranous nephropathy patients suddenly starts attacking its own kidney filters. However, it has become clear that the immune system is reacting to specific target proteins within the kidney filters. The immune system does so by producing antibodies directed against these target proteins. These antibodies play a key role in damaging the kidney filters.

Transplant patients take medication to weaken their immune system. However, despite immunosuppression, in a subset of patients, these antibodies are still produced after transplantation and may lead to recurrence.

Anti-PLA2R antibodies are immune system defense proteins that have been linked to membranous nephropathy.

Anti-PLA2R antibodies in high levels indicate active disease. They have been linked to an increased risk of worsening kidney function. Anti-PLA2R antibodies are detected in the blood of approximately 70% of people with membranous nephropathy.

Most of the research focused on the use of anti-PLA2R antibodies outside of the context of transplant.

Although research is needed, we think that screening for anti-PLA2R antibodies shortly before and after transplantation can guide in detecting recurrent disease. Moreover, when treatment for recurrence is started, anti-PLA2R antibodies may also help monitor treatment response.

Membranous nephropathy recurrence is primarily treated with a medication that breaks down the autoimmune cells that make antibodies directed against your own kidney filters. In addition, other medications are also used to help reduce the leakage of protein in the urine such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers.

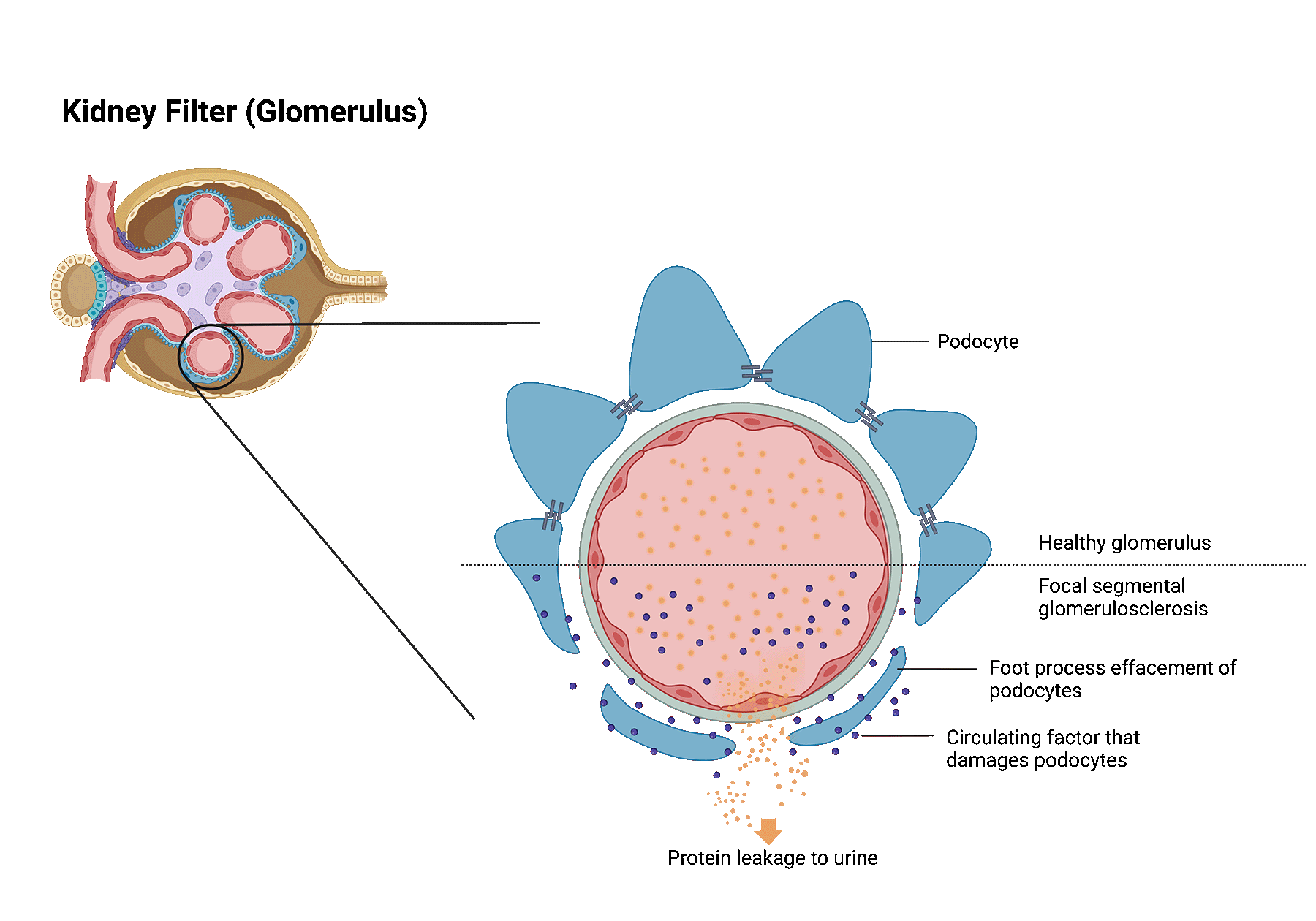

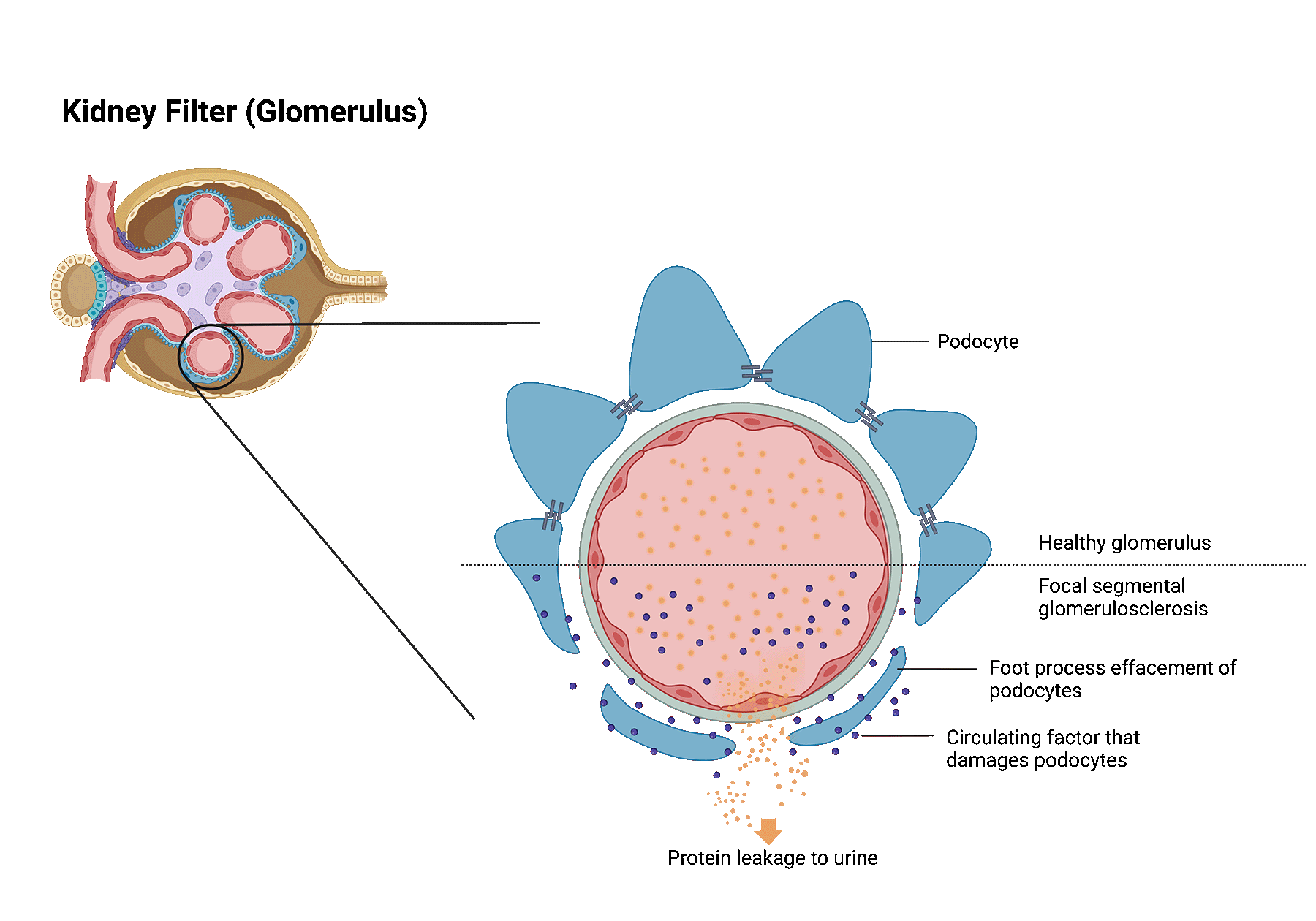

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a kidney disease in which highly specialized cells (podocytes) of the kidney filters get lost leading to glomerular scaring (sclerosis).

This scar tissue damages the filter function of the kidney, causing loss of protein in the urine. Severe loss of protein may lead to nephrotic syndrome.

Patients with nephrotic syndrome frequently develop significant swelling in addition to large amounts of protein leakage into the urine.

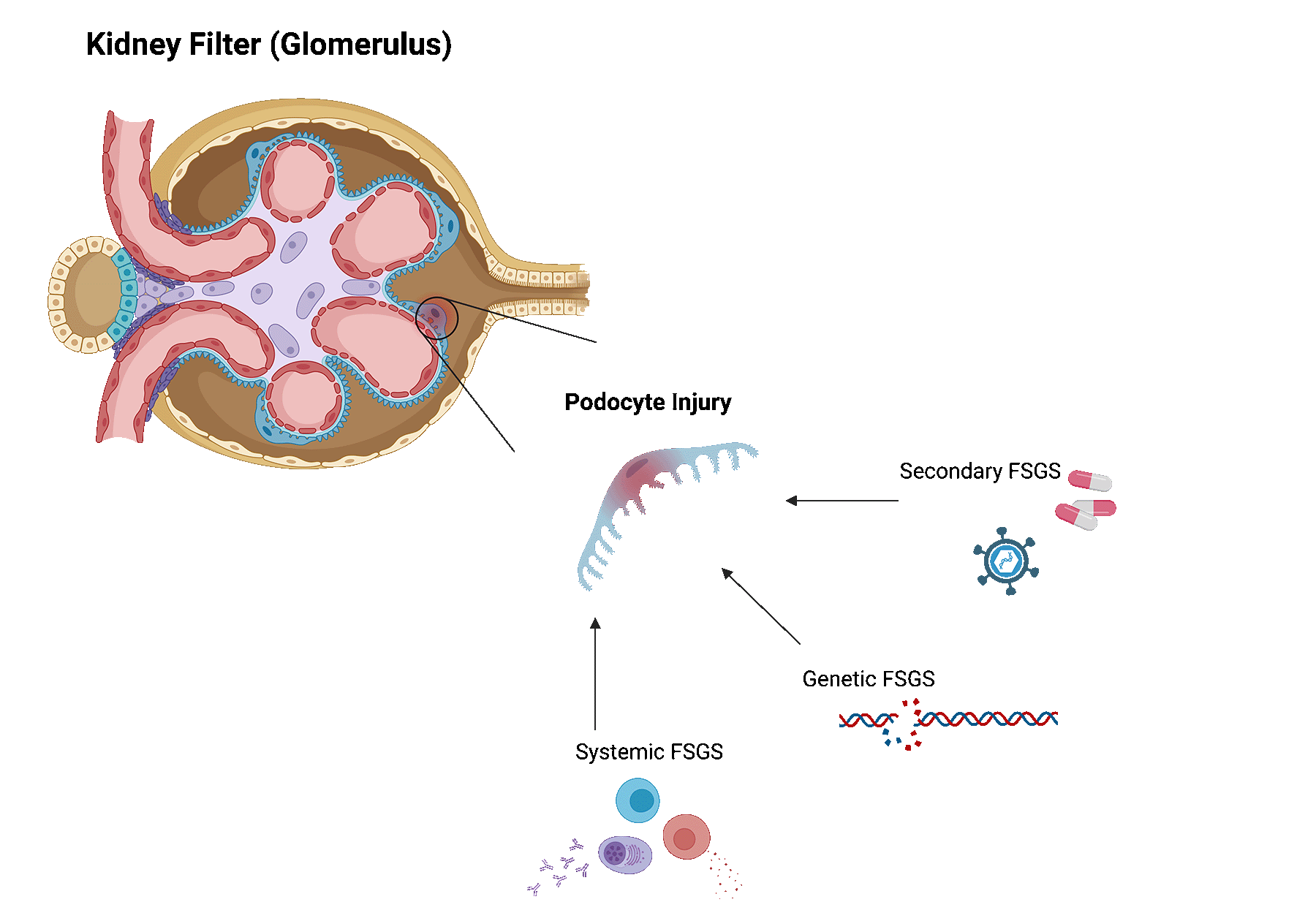

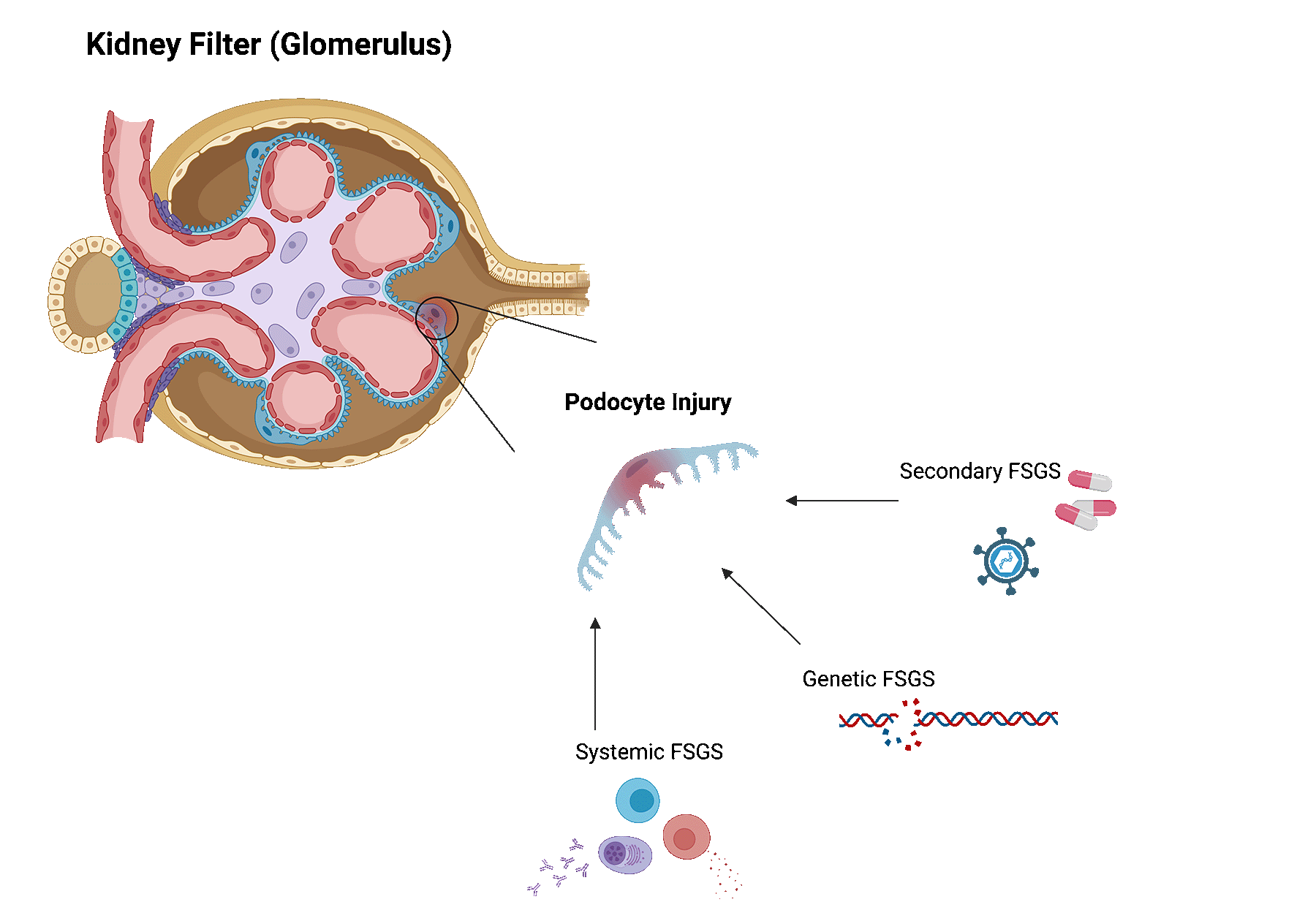

FSGS can be caused by various underlying conditions. Broadly, these can be categorized as follows.

Systemic FSGS. In this case, no clear cause can be identified. Researchers think that systemic FSGS is likely caused by dysregulations in the immune system. Some patients may be reclassified later on, as new causes are still being discovered.

Secondary FSGS. When FSGS is caused by an underlying disease or trigger, it is called secondary FSGS. Several identified diseases or triggers are viral infections, exposure to certain drugs or medications, diabetes, sickle cell disease, hypertension, another underlying kidney disease, and even obesity.

Genetic FSGS. For some patients, gene mutations that are that are important for podocytes, can lead to FSGS.

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis often recurs after transplant, varying between 30 and 60%. The risk of recurrence is dependent on several factors, including the underlying cause of FSGS.

FSGS recurrence is most often diagnosed shortly after transplantation. In rare cases, recurrence can also be diagnosed after several months or years after transplantation.

It remains unclear why FSGS recurs after transplantation.

Most patients with recurrence have systemic FSGS. There are reasons to suggest that a circulatory factor in the blood is an important contributing factor leading to both FSGS in the native kidney, and recurrence in the kidney transplant. Researchers are still not sure about the nature of this circulatory factor. Our lab is testing several different factors that may be responsible in causing FSGS recurrence. We encourage patients to help us find this circulatory factor by participating in our trial.

By analyzing health information from patients, we identified various risk factors for recurrence of FSGS.

Patients diagnosed with FSGS at an older age, had a higher risk of developing recurrent FSGS.

The BMI of patients with a recurrence was lower than of patients without recurrence.

White patients and patients with a nephrectomy of native kidneys were also more prone to develop recurrence after kidney transplantation.

Although there are some exceptions, most patients with genetic FSGS have a low risk of recurrence.

Treating patients with recurrent FSGS is very challenging, as there is no one fits all approach, and research on this topic is scarce.

Treatment most often consists of plasmapheresis and rituximab.

Plasmapheresis is a treatment in which the patient’s blood plasma is removed and replaced. This may help with removing the elusive circulatory factor from the patient’s blood.

Rituximab is an agent that depletes the immune cells that produce antibodies. These immune cells may play a key role in damaging the kidney filters.

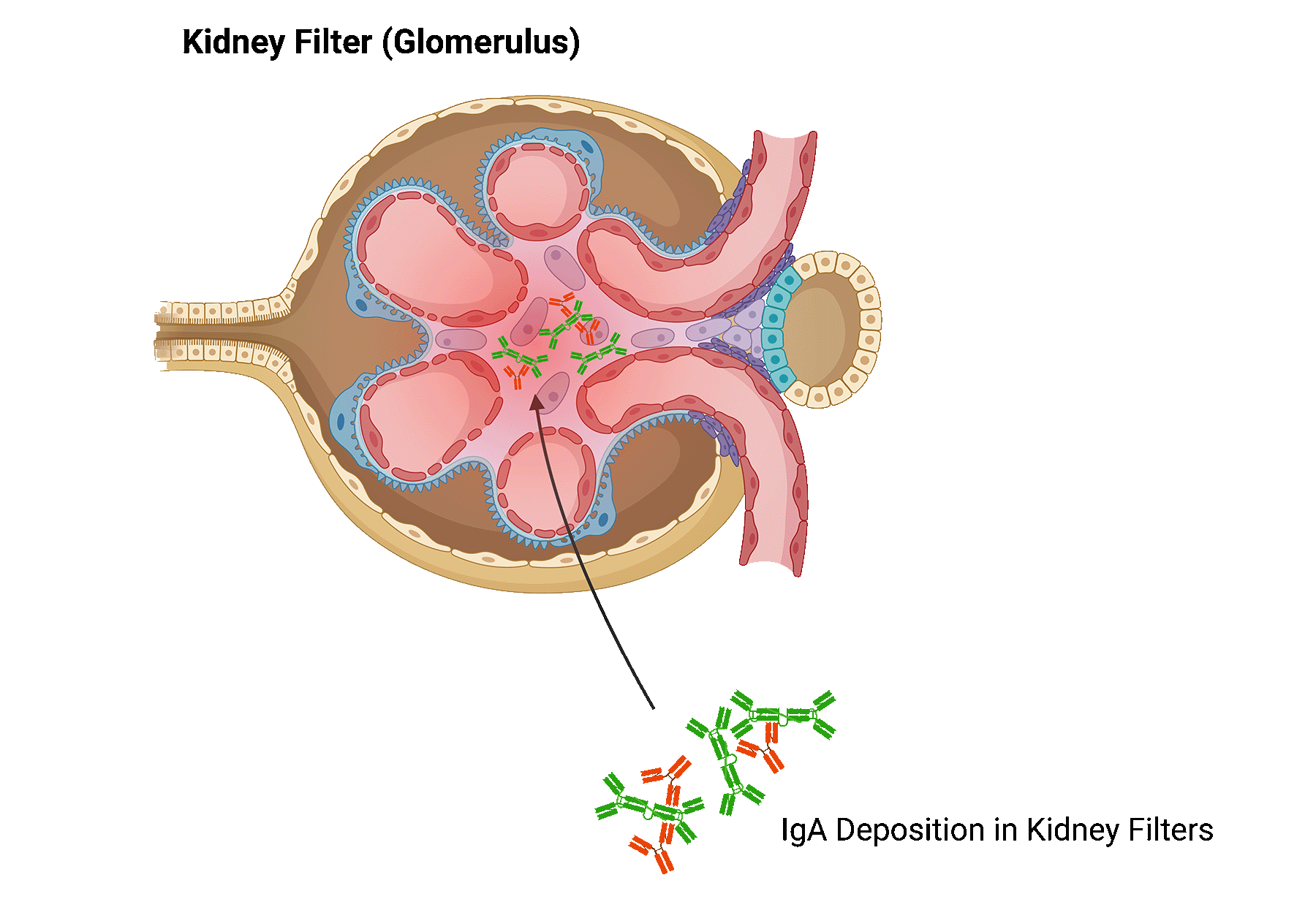

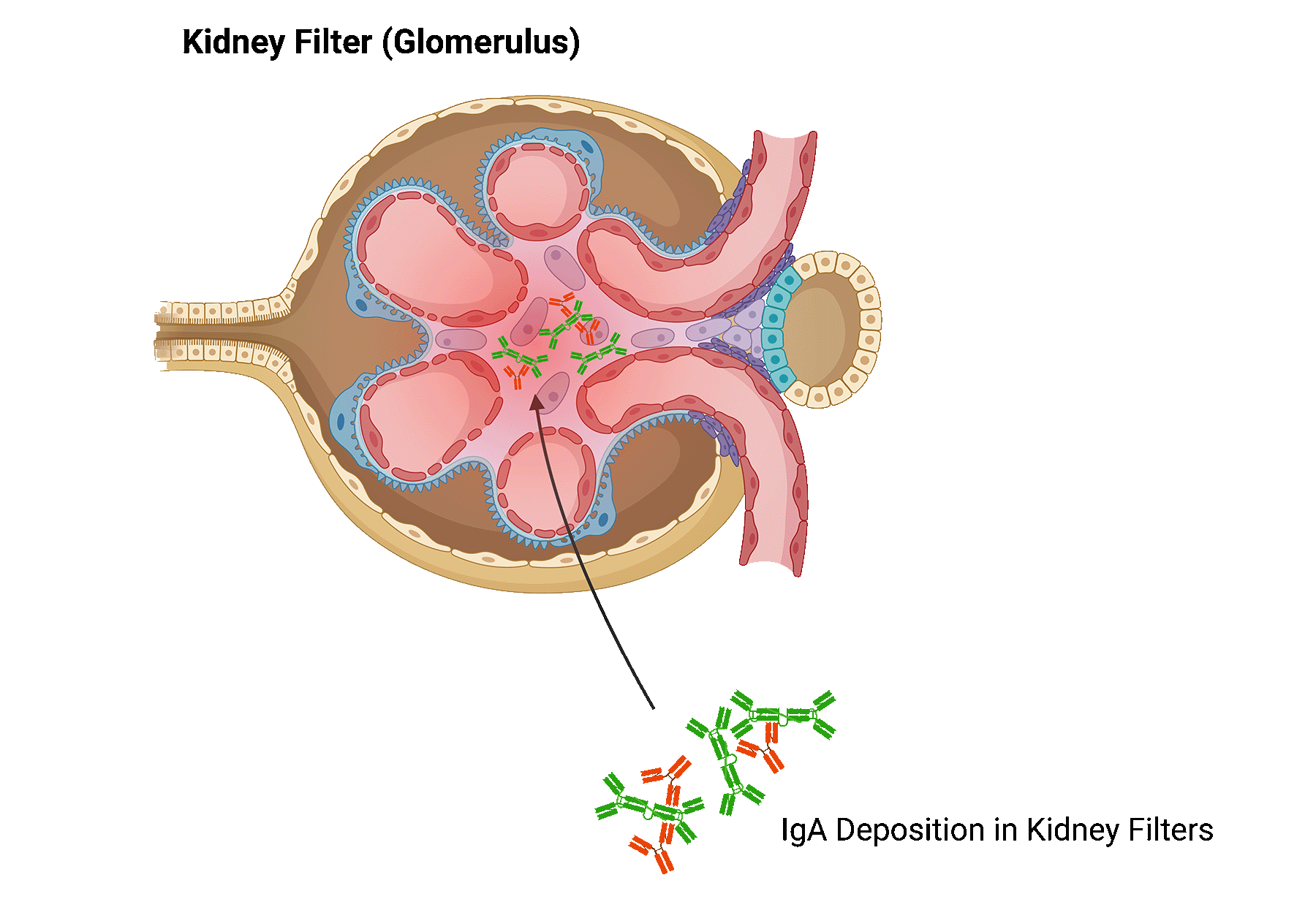

In patients with IgA nephropathy, too much of a certain antibody, called immunoglobulin A (IgA), is produced in the body. This excess of IgA builds up in the kidney, leading to inflammation and damage to kidney tissue.

Your physician will screen for underlying conditions and triggers that could cause IgA nephropathy. Potential underlying causes include chronic liver disease, celiac disease, infections, among others.

IgA nephropathy is a slowly progressive disease for most patients. In some, IgA nephropathy leads to end-stage kidney failure.

The risk of developing IgA nephropathy recurrence after transplant increases with time after transplantation and varies between 20-30%.

It remains unclear why IgA recurs in some patients, and not in others.

Using patient health information, we published the biggest study on IgA nephropathy recurrence after transplantation so far.

We found several risk factors that could increase the chance of developing recurrence.

Patients with preformed donor-specific antibodies

Patients with de novo donor specific antibodies

Patients that did not undergo dialysis before receiving their kidney transplant, had a higher risk of developing recurrent IgA nephropathy.

Donor-specific antibodies (DSA), a biomarker for rejection, appeared to be predictive of recurrence of IgA nephropathy. Our study found that patient with DSA before transplant, and DSA that forms after transplant, were at higher risk of recurrence.

There is limited information available on the best way to treat recurrent IgA nephropathy.

Medications that reduce the leakage of protein in the urine such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers may be beneficial for some patients.

There are several clinical trials investigating alternative ways to treat IgA nephropathy.

These agents act on the complement system, or involve ways to deliver steroids locally to the kidney. We encourage you to check-in with your physician to see whether you qualify for these clinical trials.

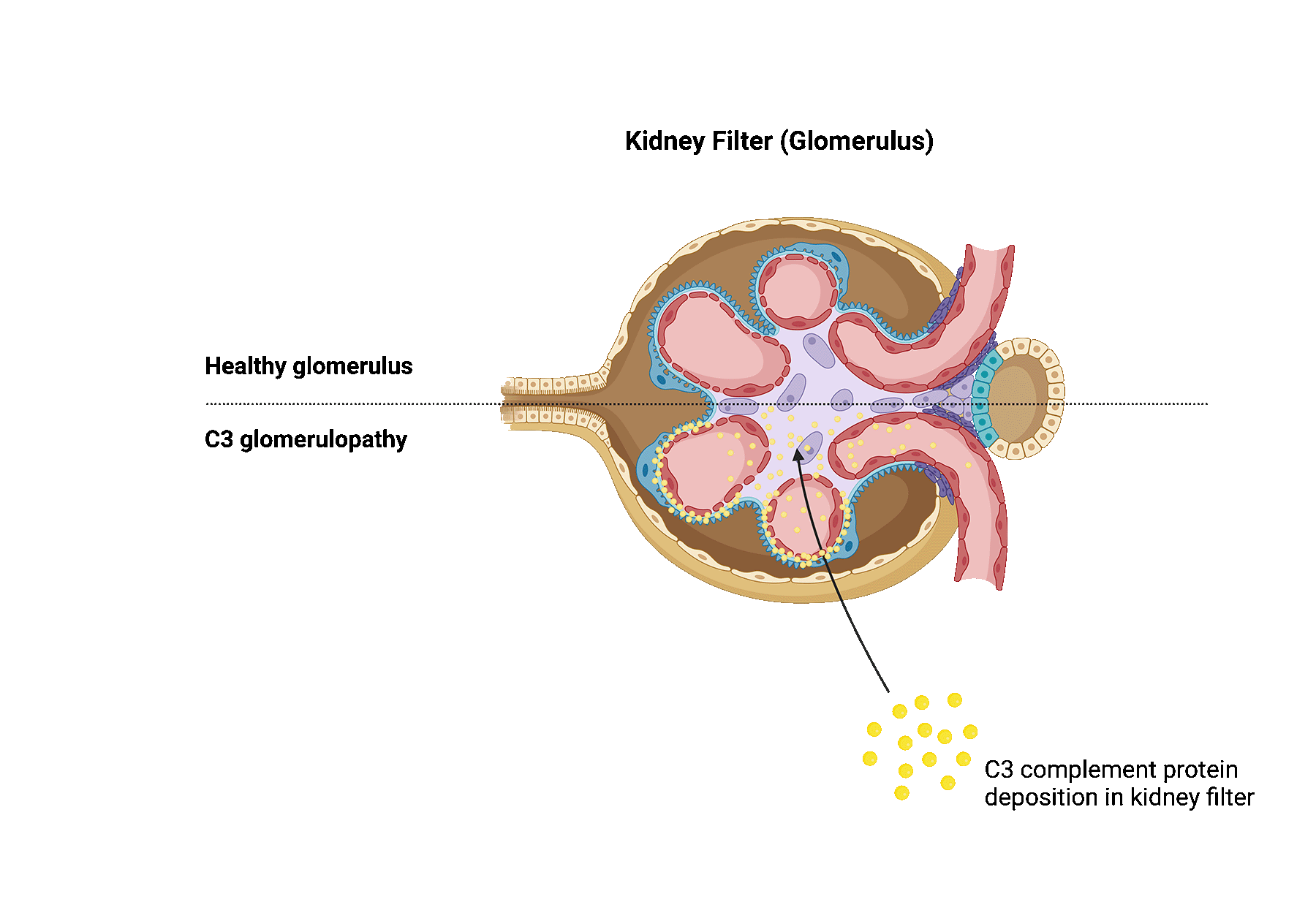

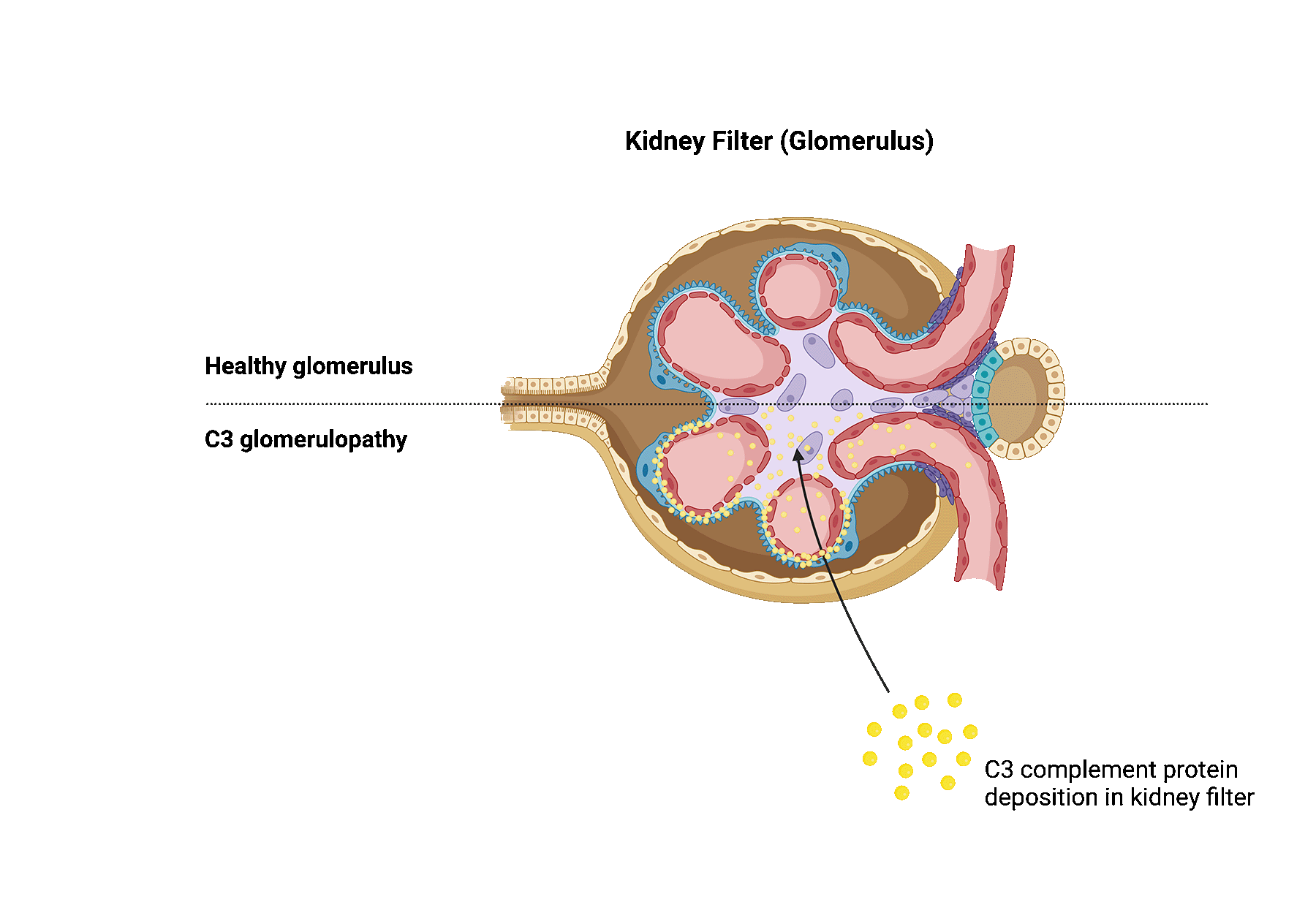

C3 glomerulopathy is a rare kidney disease that is caused by dysregulation of the complement system. The complement system is a part of the immune system and consists of several proteins in the blood that helps fight infections. In patients with C3 glomerulopathy, these proteins become abnormally activated.

C3 glomerulopathy can happen due to a variety of reasons. The complement system has several regulatory proteins in place that prevent the complement system from being overactive. Genetic mutations cause these regulatory proteins to malfunction, resulting in a dysregulated complement system.

Some patients also produce antibodies against certain complement proteins. These antibodies prevent breakdown of complement proteins and lead to overactivity of the complement system.

Complement genetic mutations may be identified in about 25% of patients.

Complement hyperactivation in C3 glomerulopathy ultimately causes damage to the kidney filters, also known as glomeruli, as well as inflammation, contributing to progressive kidney damage.

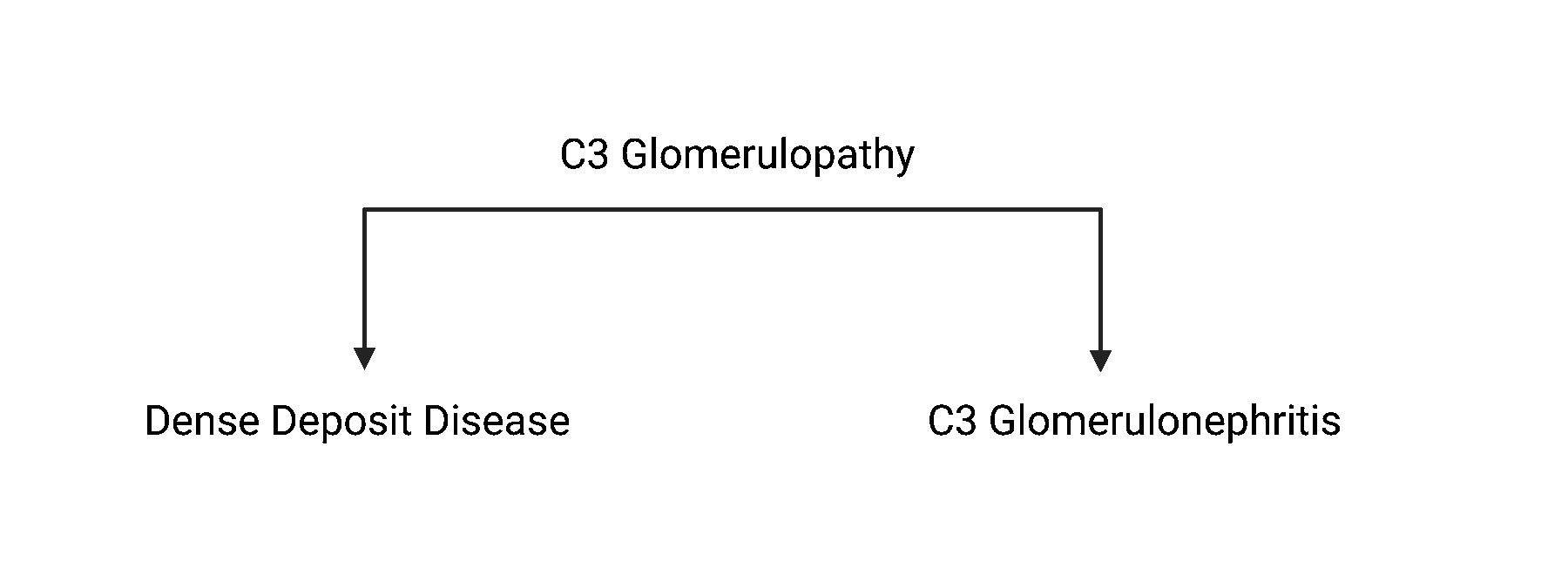

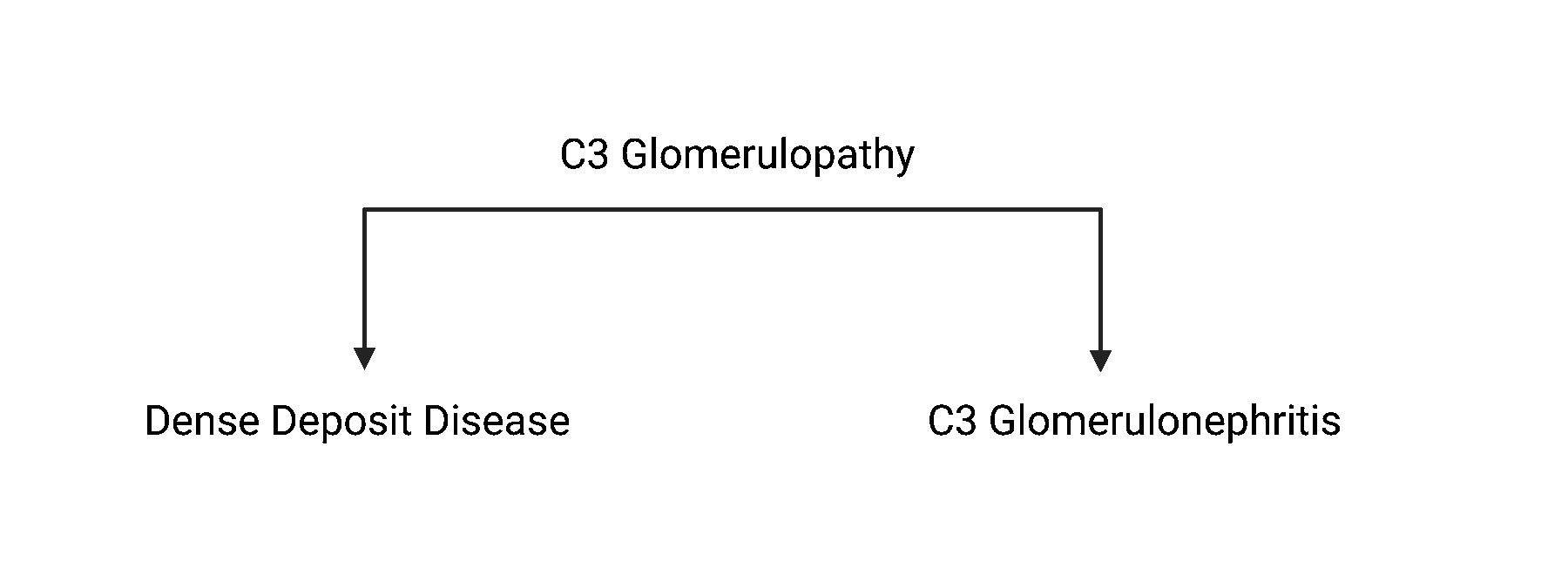

The term C3 glomerulopathy includes both dense deposit disease (DDD) and C3 glomerulonephritis (C3GN). When comparing both diseases, the damaged kidney tissue look slightly different as seen under a microscope.

Physicians decided to reclassify this C3-glomerulopathy in 2012. Before then, it was called membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN).

It remains unclear how often C3 glomerulopathy recurs after kidney transplantation. The biggest studies on this topic so far show a recurrence rate greater than 50%. Recurrence tends to occur more often in those diagnosed with DDD.

Researchers are unsure why C3 glomerulopathy recurs in some, while not in others.

By analyzing health information from patients, researchers identified various risk factors for recurrence.

Patients with cancer tend to be at higher risk for recurrence. Patients that have an aggressive disease course leading to end-stage renal failure, those with low complement levels, or high circulating antibody levels, are also more likely to develop recurrence of C3 glomerulopathy after transplant.

Treating patients with recurrent FSGS is very challenging, as there is no one fits all approach, and research on this topic is scarce.

There is little information available on the best way to treat C3 glomerulopathy. The type of treatment depends on the severity of the recurrence.

Medications that reduce the leakage of protein in the urine such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers may help.

In addition, various immunosuppressive treatments can be used. Most frequently, a form of medication affecting the complement system is prescribed.

Eculizumab is a medication that prevents complement activation. The timing and dosage of eculizumab is important to have a successful outcome.

Several ongoing trials look at alternative options to treat diseases affecting the complement system.

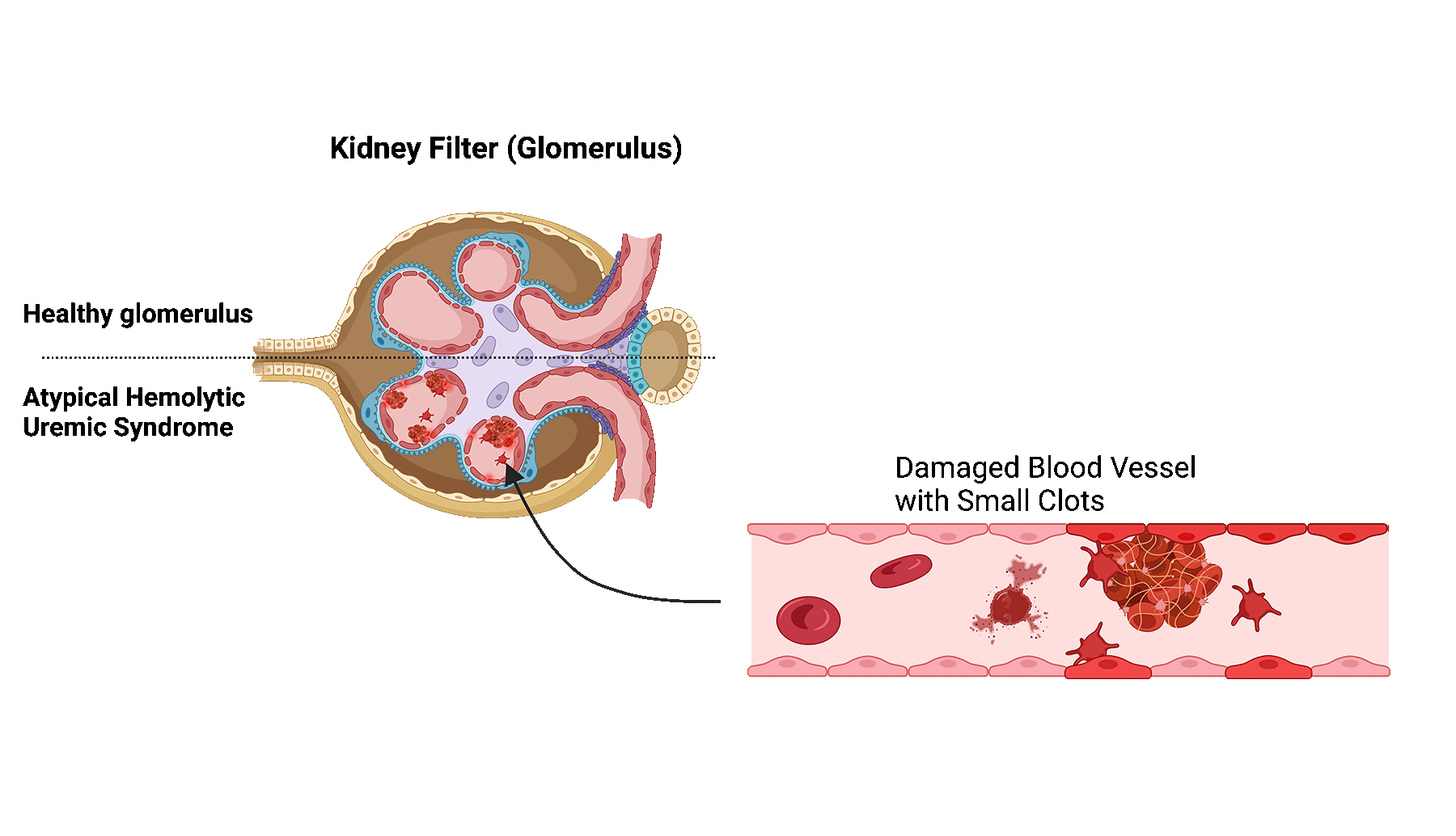

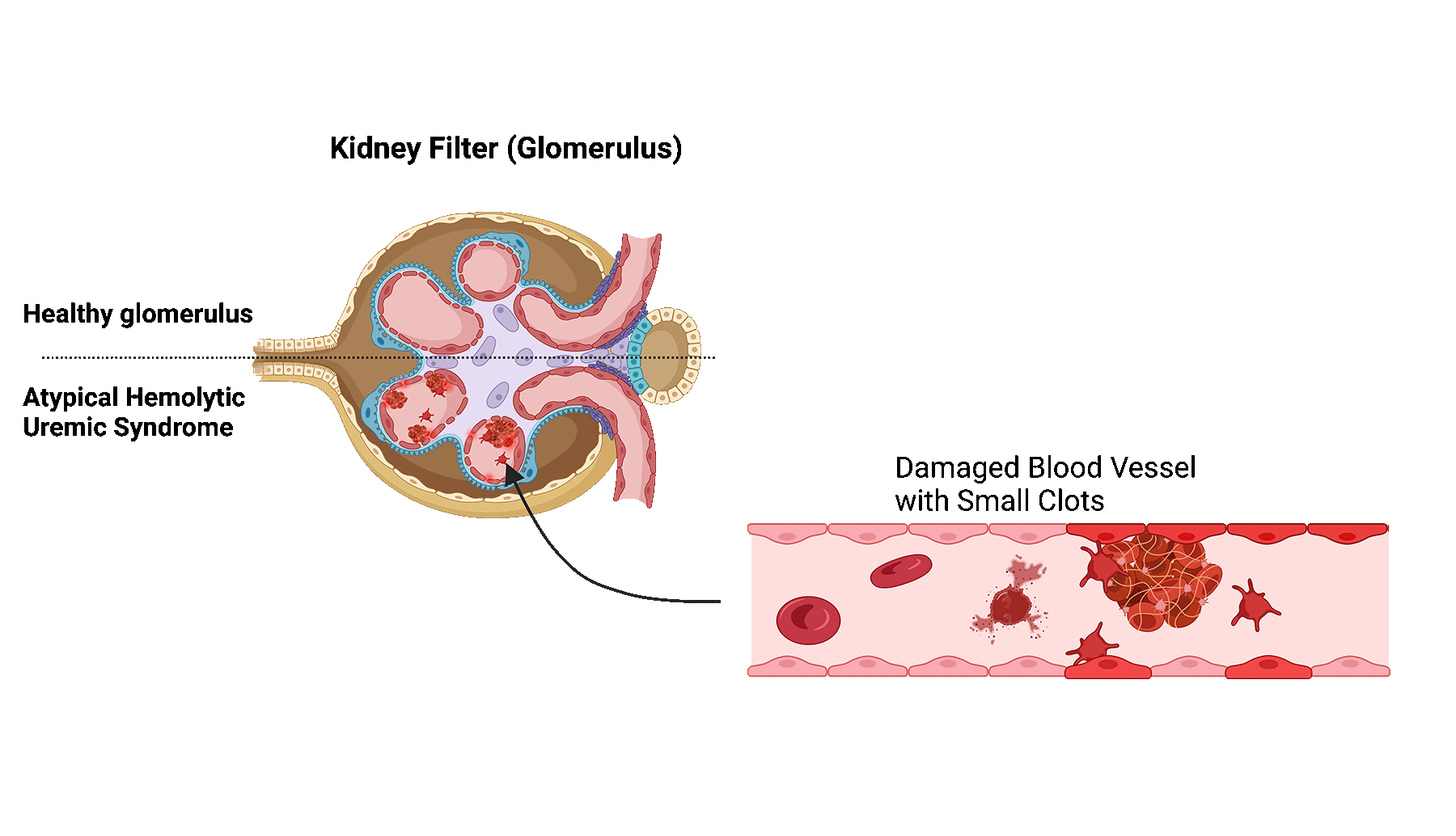

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a rare disease in which the small blood vessels of the kidneys become damaged and inflamed.

The damage and inflammation are caused by a dysregulation of the complement system. The complement system is a part of the immune system and consists of a several proteins in the blood that help fight infections.

In patients with aHUS, the proteins become abnormally activated, leading to blood clot formation and blockage of the small blood vessels in the kidney.

Blockage of these vessels limits the filtering function of the kidney filters, also known as glomeruli, ultimately leading to kidney damage.

For 60-70% of patients with aHUS, the abnormal activation of the complement system is caused by genetic mutations in the complement proteins. The most common genetic mutation, occurring in almost 30%, is related to one of the proteins called complement factor H (CFH).

Recurrence of aHUS occurs in 20%–100% of patients. The risk of recurrence is highly dependent on the underlying cause, such as a genetic mutation.

It is unknown why aHUS recurs in some, while not in others.

Patients with mutations affecting the complement proteins are especially at risk. Although these patients receive a new kidney, the mutation persists and continue to affect the complement system.

Patients with genetic mutations have a three-fold risk of recurrence compared to patients without mutations.

Many genetic mutations can cause aHUS. Some mutation have a higher risk of recurrence than others.

A mutation relating to proteins CFH, complement factor I (CFI), complement C3 (C3), and complement factor B (CFB) have a recurrence risk of 60% to 80%.

Mutations affecting the membrane cofactor protein (MCP) have a recurrence risk of around 10-20%.

The reason for this difference can be explained by the location of gene expression. If the location of gene expression is locally within the kidney, as is the case with MCP, a kidney transplant will often result in the resolution of aHUS.

However, if the genes are expressed elsewhere in the body, such as CFH and CFI which are expressed in the liver, a kidney transplant may not eliminate the problem.

Patients also have a higher risk of recurrence if they had a recurrence in previous kidney transplants.

Treating patients with recurrent aHUS is very challenging, as there is no one fits all approach, and research on this topic is scarce.

So far, aHUS is most often treated with a combination of plasmapheresis and eculizumab.

Plasmapheresis is a treatment in which the patient’s blood plasma is removed and replaced.

Eculizumab is a medication that binds to a part of the immune system, preventing it to be activated and cause damage. The timing and dosage of eculizumab is important to have a successful outcome.

Several ongoing trials look at alternative options to treat diseases affecting the complement system.

Glomerular disease describes a process in which the kidney’s filters, also known as the glomeruli, are injured.

Although highly dependent on the underlying cause, certain glomerular diseases can progress to end-stage kidney disease, requiring patients to receive a transplant or initiate dialysis.

A kidney transplant is the best treatment option for most patients with end-stage kidney disease. Unfortunately, a transplant is not considered a cure for glomerular disease patients, as recurrence following kidney transplantation may occur.

The recurrence of glomerular disease often damages the transplanted kidney, shortening its lifespan.

Preventing glomerular disease recurrence in causing injury to the newly transplanted kidney still represents one of the biggest challenges for clinicians and scientists worldwide.

The frequency and impact of recurrence after transplantation are highly dependent on the subtype of glomerular disease that led to the failure of the patient’s native kidneys.

Below, find out more about the most common glomerular disease subtypes that can recur after transplant.

Glomerular disease recurrence is frequently asymptomatic and only suspected by a change in specific blood and/or urine tests. In more aggressive cases, a patient may present with the following:

Membranous nephropathy is one of the most common causes of nephrotic syndrome in western countries. In patients with membranous nephropathy, the autoimmune system turns against the tiny filters of the kidneys (aka, glomeruli). Normally, the kidney filters are responsible for filtering toxins and removing extra fluids from the blood, while preventing the passage of most proteins into the urine. When the kidney filters are injured, loss of protein into the urine may occur and when severe, may lead to a syndrome called nephrotic syndrome.

Patients with nephrotic syndrome frequently develop significant swelling in addition to large amounts of protein leakage into the urine.

Despite treatment, almost one-third of patients with membranous nephropathy develop kidney failure.

It is estimated that membranous nephropathy recurs in 30% of patients that received a transplant. Recurrence is most often diagnosed within the first few years after transplantation. The best way to identify membranous nephropathy recurrence in the transplanted kidney is through a kidney biopsy.

It is still poorly understood why the immune system in membranous nephropathy patients suddenly starts attacking its own kidney filters. However, it has become clear that the immune system is reacting to specific target proteins within the kidney filters. The immune system does so by producing antibodies directed against these target proteins. These antibodies play a key role in damaging the kidney filters.

Transplant patients take medication to weaken their immune system. However, despite immunosuppression, in a subset of patients, these antibodies are still produced after transplantation and may lead to recurrence.

Anti-PLA2R antibodies are immune system defense proteins that have been linked to membranous nephropathy.

Anti-PLA2R antibodies in high levels indicate active disease. They have been linked to an increased risk of worsening kidney function. Anti-PLA2R antibodies are detected in the blood of approximately 70% of people with membranous nephropathy.

Most of the research focused on the use of anti-PLA2R antibodies outside of the context of transplant.

Although research is needed, we think that screening for anti-PLA2R antibodies shortly before and after transplantation can guide in detecting recurrent disease. Moreover, when treatment for recurrence is started, anti-PLA2R antibodies may also help monitor treatment response.

Membranous nephropathy recurrence is primarily treated with a medication that breaks down the autoimmune cells that make antibodies directed against your own kidney filters. In addition, other medications are also used to help reduce the leakage of protein in the urine such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers.

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a kidney disease in which highly specialized cells (podocytes) of the kidney filters get lost leading to glomerular scaring (sclerosis).

This scar tissue damages the filter function of the kidney, causing loss of protein in the urine. Severe loss of protein may

lead to nephrotic syndrome.

Patients with nephrotic syndrome frequently develop significant swelling in addition to large amounts of protein leakage into the urine.

FSGS can be caused by various underlying conditions. Broadly, these can be categorized as follows.

Systemic FSGS. In this case, no clear cause can be identified. Researchers think that systemic FSGS is likely caused by dysregulations in the immune system. Some patients may be reclassified later on, as new causes are still being discovered.

Secondary FSGS. When FSGS is caused by an underlying disease or trigger, it is called secondary FSGS. Several identified diseases or triggers are viral infections, exposure to certain drugs or medications, diabetes, sickle cell disease, hypertension, another underlying kidney disease, and even obesity.

Genetic FSGS. For some patients, gene mutations that are that are important for podocytes, can lead to FSGS.

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis often recurs after transplant, varying between 30 and 60%. The risk of recurrence is dependent on several factors, including the underlying cause of FSGS.

FSGS recurrence is most often diagnosed shortly after transplantation. In rare cases, recurrence can also be diagnosed after several months or years after transplantation.

It remains unclear why FSGS recurs after transplantation.

Most patients with recurrence have systemic FSGS. There are reasons to suggest that a circulatory factor in the blood is an important contributing factor leading to both FSGS in the native kidney, and recurrence in the kidney transplant. Researchers are still not sure about the nature of this circulatory factor. Our lab is testing several different factors that may be responsible in causing FSGS recurrence. We encourage patients to help us find this circulatory factor by participating in our trial.

By analyzing health information from patients, we identified various risk factors for recurrence of FSGS.

Patients diagnosed with FSGS at an older age, had a higher risk of developing recurrent FSGS.

The BMI of patients with a recurrence was lower than of patients without recurrence.

White patients and patients with a nephrectomy of native kidneys were also more prone to develop recurrence after kidney transplantation.

Although there are some exceptions, most patients with genetic FSGS have a low risk of recurrence.

Treating patients with recurrent FSGS is very challenging, as there is no one fits all approach, and research on this topic is scarce.

Treatment most often consists of plasmapheresis and rituximab.

Plasmapheresis is a treatment in which the patient’s blood plasma is removed and replaced. This may help with removing the elusive circulatory factor from the patient’s blood.

Rituximab is an agent that depletes the immune cells that produce antibodies. These immune cells may play a key role in damaging the kidney filters.

Toggle

In patients with IgA nephropathy, too much of a certain antibody, called immunoglobulin A (IgA), is produced in the body. This excess of IgA builds up in the kidney, leading to inflammation and damage to kidney tissue.

Your physician will screen for underlying conditions and triggers that could cause IgA nephropathy. Potential underlying causes include chronic liver disease, celiac disease, infections, among others.

IgA nephropathy is a slowly progressive disease for most patients. In some, IgA nephropathy leads to end-stage kidney failure.

The risk of developing IgA nephropathy recurrence after transplant increases with time after transplantation and varies between 20-30%.

It remains unclear why IgA recurs in some patients, and not in others.

Using patient health information, we published the biggest study on IgA nephropathy recurrence after transplantation so far.

We found several risk factors that could increase the chance of developing recurrence.

Patients with preformed donor-specific antibodies

Patients with de novo donor specific antibodies

Patients that did not undergo dialysis before receiving their kidney transplant, had a higher risk of developing recurrent IgA nephropathy.

Donor-specific antibodies (DSA), a biomarker for rejection, appeared to be predictive of recurrence of IgA nephropathy. Our study found that patient with DSA before transplant, and DSA that forms after transplant, were at higher risk of recurrence.

There is limited information available on the best way to treat recurrent IgA nephropathy.

Medications that reduce the leakage of protein in the urine such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers may be beneficial for some patients.

There are several clinical trials investigating alternative ways to treat IgA nephropathy.

These agents act on the complement system, or involve ways to deliver steroids locally to the kidney. We encourage you to check-in with your physician to see whether you qualify for these clinical trials.

Content

C3 glomerulopathy is a rare kidney disease that is caused by dysregulation of the complement system. The complement system is a part of the immune system and consists of several proteins in the blood that helps fight infections. In patients with C3 glomerulopathy, these proteins become abnormally activated.

C3 glomerulopathy can happen due to a variety of reasons. The complement system has several regulatory proteins in place that prevent the complement system from being overactive. Genetic mutations cause these regulatory proteins to malfunction, resulting in a dysregulated complement system.

Some patients also produce antibodies against certain complement proteins. These antibodies prevent breakdown of complement proteins and lead to overactivity of the complement system.

Complement genetic mutations may be identified in about 25% of patients.

Complement hyperactivation in C3 glomerulopathy ultimately causes damage to the kidney filters, also known as glomeruli, as well as inflammation, contributing to progressive kidney damage.

The term C3 glomerulopathy includes both dense deposit disease (DDD) and C3 glomerulonephritis (C3GN). When comparing both diseases, the damaged kidney tissue look slightly different as seen under a microscope.

Physicians decided to reclassify this C3-glomerulopathy in 2012. Before then, it was called membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN).

It remains unclear how often C3 glomerulopathy recurs after kidney transplantation. The biggest studies on this topic so far show a recurrence rate greater than 50%. Recurrence tends to occur more often in those diagnosed with DDD.

Researchers are unsure why C3 glomerulopathy recurs in some, while not in others.

By analyzing health information from patients, researchers identified various risk factors for recurrence.

Patients with cancer tend to be at higher risk for recurrence. Patients that have an aggressive disease course leading to end-stage renal failure, those with low complement levels, or high circulating antibody levels, are also more likely to develop recurrence of C3 glomerulopathy after transplant.

Treating patients with recurrent FSGS is very challenging, as there is no one fits all approach, and research on this topic is scarce.

There is little information available on the best way to treat C3 glomerulopathy. The type of treatment depends on the severity of the recurrence.

Medications that reduce the leakage of protein in the urine such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers may help.

In addition, various immunosuppressive treatments can be used. Most frequently, a form of medication affecting the complement system is prescribed.

Eculizumab is a medication that prevents complement activation. The timing and dosage of eculizumab is important to have a successful outcome.

Several ongoing trials look at alternative options to treat diseases affecting the complement system.

Toggle Content

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a rare disease in which the small blood vessels of the kidneys become damaged and inflamed.

The damage and inflammation are caused by a dysregulation of the complement system. The complement system is a part of the immune system and consists of a several proteins in the blood that help fight infections.

In patients with aHUS, the proteins become abnormally activated, leading to blood clot formation and blockage of the small blood vessels in the kidney.

Blockage of these vessels limits the filtering function of the kidney filters, also known as glomeruli, ultimately leading to kidney damage.

For 60-70% of patients with aHUS, the abnormal activation of the complement system is caused by genetic mutations in the complement proteins. The most common genetic mutation, occurring in almost 30%, is related to one of the proteins called complement factor H (CFH).

Recurrence of aHUS occurs in 20%–100% of patients. The risk of recurrence is highly dependent on the underlying cause, such as a genetic mutation.

It is unknown why aHUS recurs in some, while not in others.

Patients with mutations affecting the complement proteins are especially at risk. Although these patients receive a new kidney, the mutation persists and continue to affect the complement system.

Patients with genetic mutations have a three-fold risk of recurrence compared to patients without mutations.

Many genetic mutations can cause aHUS. Some mutation have a higher risk of recurrence than others.

A mutation relating to proteins CFH, complement factor I (CFI), complement C3 (C3), and complement factor B (CFB) have a recurrence risk of 60% to 80%.

Mutations affecting the membrane cofactor protein (MCP) have a recurrence risk of around 10-20%.

The reason for this difference can be explained by the location of gene expression. If the location of gene expression is locally within the kidney, as is the case with MCP, a kidney transplant will often result in the resolution of aHUS.

However, if the genes are expressed elsewhere in the body, such as CFH and CFI which are expressed in the liver, a kidney transplant may not eliminate the problem.

Patients also have a higher risk of recurrence if they had a recurrence in previous kidney transplants.

Treating patients with recurrent aHUS is very challenging, as there is no one fits all approach, and research on this topic is scarce.

So far, aHUS is most often treated with a combination of plasmapheresis and eculizumab.

Plasmapheresis is a treatment in which the patient’s blood plasma is removed and replaced.

Eculizumab is a medication that binds to a part of the immune system, preventing it to be activated and cause damage. The timing and dosage of eculizumab is important to have a successful outcome.

Several ongoing trials look at alternative options to treat diseases affecting the complement system.